Harriet C. Ijeomah

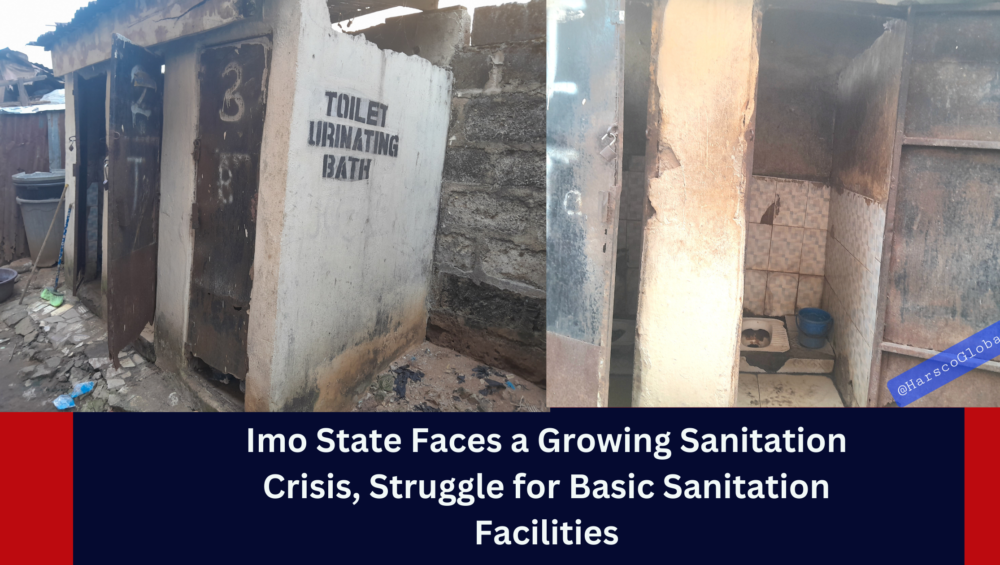

In Imo State, the lack of public toilets has become an urgent public health issue, particularly in busy markets and urban centers. This challenge, compounded by the absence of public sanitation facilities, has forced residents to resort to unsafe and unhealthy alternatives. The state, once home to several government-owned public toilets, has seen these amenities disappear, especially following the fire that destroyed the “Ekeonuwa” local market in 2017.

For many in the state, the absence of sanitation facilities has forced them to make desperate choices. Okechukwu Mbakwe, a businessman, highlights the severe impact of this lack of infrastructure. “Since the market was destroyed, there have been no public toilets. Most of the time, we struggle to find a place to relieve ourselves,” Mbakwe shared. “At times, we hold it for hours, which has health implications.”

The absence of public toilets, especially in high-traffic areas such as markets, schools, and busy streets, is not only inconvenient but a significant health risk. According to Mbakwe, there is a pressing need to build public toilets in strategic locations across the state to prevent the growing public health crisis.

Health Risks from Poor Sanitation

The lack of sanitation facilities in Imo State mirrors a larger issue across Nigeria. According to recent statistics from the World Health Organization (WHO), an estimated 3.5 billion people globally lack access to safely managed sanitation services, with 1.5 billion lacking even basic sanitation services. The implications of poor sanitation are clear: open defecation continues to be a major contributor to the spread of preventable diseases such as cholera, diarrhea, and dysentery—diseases that disproportionately affect children and vulnerable populations.

In Imo State, the situation is dire. Many residents, including business owners like Claire Effiong, have become accustomed to the daily struggle of finding clean and accessible toilets. “Whenever nature calls, I have to plead with shop owners to let me use their restrooms,” Effiong lamented. “But not everyone is willing to help, and those who do often do so reluctantly. Sometimes, I can’t find a clean toilet.”

The state’s reliance on private toilets further exacerbates the problem. According to Emmanuel Amaefula, the market chairman, many businesses have toilets, but these are typically reserved for shop owners and their employees. “Public toilets are mostly owned by private individuals, and they charge a fee for use,” he said. “It costs 100 naira to urinate and 200 naira to defecate. These facilities are mostly available only for individuals aged eight and above, which limits access for younger children.”

A Lack of Options for Mothers and Children

One of the most concerning aspects of this sanitation crisis is the impact on young children and mothers. A nursing mother who spoke with Harsco Global on the condition of anonymity explained the improvised methods she uses for her young child’s sanitation needs. “I have to let my child defecate in plastic bags and dispose of them in nearby waste dumps,” she shared. “Other mothers often rely on diapers, but they’re expensive and not always an ideal solution.”

The absence of public toilets for children, especially in markets and public spaces, underlines the need for inclusive and accessible sanitation facilities for all residents.

Addressing the Sanitation Crisis: The Call for Action

The GoodWash Foundation for Health and Environmental Protection, a local nonprofit Organisation, has been vocal about the need to address open defecation and improve access to public sanitation facilities. The Executive Director of the Foundation, Ikenna Anumnu, stressed that while awareness is growing, the government’s role in ensuring the construction and maintenance of public toilets cannot be overstated. “We need more awareness campaigns that show people the dangers of open defecation. But the government must also take responsibility,” he said. “Public sanitation facilities need to be inclusive, accessible, and properly maintained. That means considering the needs of women, children, and people with disabilities.”

For Ikenna and other advocates, the solution lies in both infrastructure and awareness. “Sanitation is a basic human right,” he added. “It’s not just about building toilets but ensuring that they’re available and usable by everyone, including people with disabilities. Proper sanitation should be non-negotiable.”

The Way Forward: Ensuring Access to Safe Sanitation

The global sanitation crisis cannot be ignored. According to the United Nations, while 2.5 billion people have gained access to safely managed sanitation services since 2000, an estimated 3.5 billion people are still without them. The figures are alarming, especially when considering that over 400 million people still practice open defecation.

In Nigeria, these global statistics are mirrored in states like Imo, where public sanitation facilities are either insufficient or non-existent. As Nigeria works toward achieving Sustainable Development Goal 6, which aims to provide universal access to clean water and sanitation by 2030, it is crucial that local governments like Imo take a leading role in addressing these challenges.

To move forward, the state government must prioritize the construction of public toilets in high-traffic areas and ensure these facilities are well-maintained. Public education on the dangers of open defecation must also be strengthened, especially in rural and underserved areas.

In conclusion, Imo State’s sanitation crisis demands immediate action. Building more public toilets, raising awareness about the importance of sanitation, and making facilities accessible to all residents—regardless of age, gender, or ability—are critical steps in ensuring a healthier, safer future for everyone in the state.